**This review was contributed by another new guest author, Thunderfist, who takes his name from the hero of C.S. Lewis' classic travelogue "A Horse and His Boy." Enjoy!**

Although Howards End is one of my favorite books, it often slips my mind when I think about English literature. Part of the reason for this is that its author, E. M. Forster, occupies an in-between time in world history: the close of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. Victorianism was on the wane but World War One had yet to destroy Victorian and Romantic ideals. In a sense, Forster’s oeuvre in general reflects this transition: A Room with a View, published in 1908, is a novel of the nineteenth century, a traditional comedy of manners set in Italy and pastoral England. Published eighteen years later, A Passage to India is a dispassionate, modern depiction of British colonialism in India. Separating these two novels in the oeuvre is only Howards End, which captures the poignant transition between two very different centuries.

Although Howards End is one of my favorite books, it often slips my mind when I think about English literature. Part of the reason for this is that its author, E. M. Forster, occupies an in-between time in world history: the close of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. Victorianism was on the wane but World War One had yet to destroy Victorian and Romantic ideals. In a sense, Forster’s oeuvre in general reflects this transition: A Room with a View, published in 1908, is a novel of the nineteenth century, a traditional comedy of manners set in Italy and pastoral England. Published eighteen years later, A Passage to India is a dispassionate, modern depiction of British colonialism in India. Separating these two novels in the oeuvre is only Howards End, which captures the poignant transition between two very different centuries.

I have a long history with Forster: when I was fifteen I watched the classic film adaptation of A Room with a View and fell in love with its gorgeous portrayal of Edwardian England. From the rich and ceremonious dinners to the long sweeping gowns to the gaslamps and open carriages, A Room with a View is a period piece par excellence. The novel is a delight of witty dialogue and tongue-in-cheek narrative, following the tradition of Jane Austen. It portrays a sunny world of youth in which relational conflicts are easily cleared up with heart-to-heart honesty and a final surrender to true love; and its characters play tennis, drink tea and go on picnics in Arcadian countryside scenes.

In a conversation with the Supreme Arbitress of Taste, we agreed that A Room with a View is a novel of Forster’s youth whereas Howards End is a novel of his maturity. Written only two years later, Howards End is set in cosmopolitan London and focuses on a cultured, artistic family of two sisters and one brother. In an echo of Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, the older sister, Margaret, is a sensible woman who tempers her deep feelings with practicality, and the younger sister, Helen, is an emotional and romantic woman whose feelings draw her into other people’s troubles. These women become friends with two very different families: the rich and businesslike Wilcoxes and the poor, struggling, but sensitive and artistic Leonard Bast and his wife. Both families draw on the Schlegels’ sympathy: Mr. Wilcox loses his wife, Ruth (also a friend of Margaret’s), and Leonard Bast is threatened with hopeless poverty and unemployment. The famous epigram of the novel is “Only connect…” and the novel is indeed about different isolated clans within the social and economic structure of England, whose only connection is the Schlegels.

The Schlegel girls occupy a place of freedom in the novel because they were born independently wealthy and have never been exposed to the hard, pragmatic aspect of making money. As their loyalties to the Wilcox and Bast families are taxed by love and misfortune, the underlying truths about both love and loyalty, about romantic ideals and real life, are questioned. At the center of the novel is a house, Howards End, a little old country house that becomes a point of contention between the Schlegels and the Wilcoxes: it belongs to Mr. Wilcox but, as his wife’s property, is left to Margaret upon her death in a note. At a glance, the novel seems like a large jigsaw puzzle with the pieces easily fitted into place: Howards End represents England and the three families respectively represent the business class, the artisans, and the common folk. Who will inherit England?

But Howards End, both the novel and the house it takes its name from, are much more than that. They are an emotional and spiritual evocation of England and the people who already live in her, none of whom really “own” her but who must fight for and against each other in the struggle to love her, preserve her, and change her. That Forster wrote the novel in 1910, only four years before the First World War, adds an unintentional poignancy to the story: for this world in which the families’ struggle takes place is itself on the brink of traumatic change.

Howards End, though not considered Forster’s greatest novel academically, is probably his most famous and popular. The epigram “Only connect…” is deservedly often alluded to by the literary world, and contemporary British author Zadie Smith wrote her novel On Beauty as an homage to Howards End. In this sense, “Only connect…” functions quite literally, for Forster’s novel indeed forges connections across centuries and different literary movements, from Austen’s neoclassical Sense and Sensibility to Smith’s postmodern On Beauty.

Of course, the real worth of Howards End lies simply in its literary beauty. Forster’s turns-of-phrase, his descriptions and his superb characterizations give Howards End a poetic depth that is both modern and timeless. It is Forster’s swansong, his elegant, elegiac depiction of a world caught between Romanticism and Modernism, ideals and disillusionment, love and family loyalty, single-minded truths and over-arching truths. It precipitates Modernism with its own simplified but still romantic style, forging a beautiful complement to both past and future literary movements while avoiding complete attribution to either.

After this glowing review, I must admit I have mixed feelings about Forster. He has a distinctive voice that sometimes grabs me and sometimes leaves me cold. Only three of his stories resonate with me, and of those three A Passage to India, often deemed his greatest work, is a story I admire while finding it difficult to read. Forster’s early work has never caught my interest, but these last three novels, and for me personally A Room with a View and Howards End, achieve a particular kind of gorgeousness that comes from the very Forsterian voice that I occasionally have trouble with. In these two novels Forster's style becomes not only admirable but deeply touching. A Room with a View, whatever its immaturity, is nonetheless a perennially lovable romantic comedy; and Howards End achieves a quiet greatness with its subtle and graceful insights.

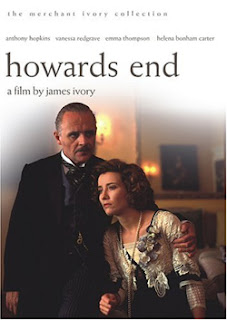

As an addendum, Merchant-Ivory’s film adaptations of A Room with a View (1986) and Howards End (1991) both rank as some of the best film adaptations I’ve ever seen. David Lean’s version of A Passage to India (1984) is also well worth watching.

No comments:

Post a Comment